18 Oct New crises, same resilience?

On 24 February 2022 at the latest, a long-simmering crisis in Europe became acute. Since this day, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has had a wide range of direct and indirect effects on people’s everyday lives across Europe. Recent surveys by COVINFORM partner SINUS-Institut answers some key questions about the overlapping impacts of the Ukraine war and the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Does the war and its economic impact mean that Germans are no longer concerned about COVID? In this blog post, SINUS-Institut summarizes findings based on nationally representative surveys in Germany conducted between April and June 2022.

The COVID pandemic has slipped down the list of Germans’ concerns, as reflected in our representative online survey conducted at the end of April / beginning of May 2022. Germans have been much more concerned about the war in Ukraine – and especially about its various effects that can be felt directly in their everyday lives. However, for the less-privileged in particular, the socioeconomic impacts and risks imposed by COVID (loss of income, potential future lockdowns, etc.) and the war (higher prices, an energy-insecure winter, etc.) converge to degrade overall quality of life. Both crises have also aggravated social polarization, negatively affecting personal relationships for more than one out of four Germans.

Major existential worries – particularly in the less privileged milieus

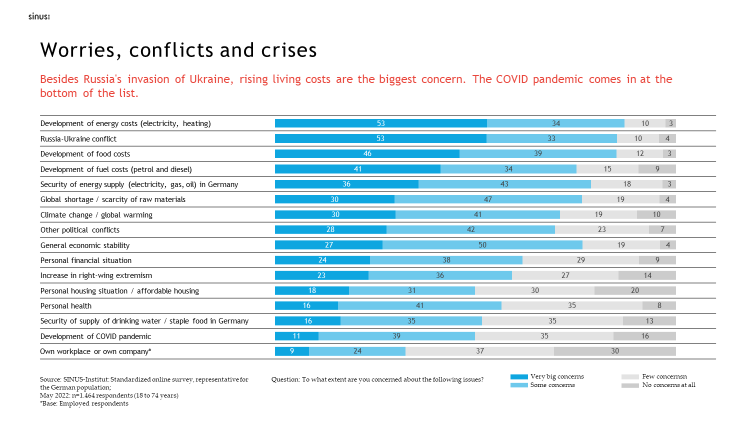

Currently, Germans’ most pronounced concerns are the cost and supply issues related to the war in Ukraine. Around 87% of Germans are concerned about rising energy prices; 85% about food prices; and 75% about fuel prices. Energy and raw material shortages are of concern to 79% and 77% of the population, respectively. Concern about the war itself, which ultimately causes all of these crises, sits just below energy prices at 85%.

The different ways people prioritise concerns and fears are strongly related to their social position and milieu affiliation. This is shown by analysis according to the Sinus-Milieu model, which categorizes the German population into ten social milieus, or “groups of like-minded people,” based on their social position on the one hand, and their basic values and views of life on the other (Barth et al. 2018; cf. Schulze 1992; Hradil 2007; Vester 2009; Reckwitz 2021) [1].

In the high-status milieus, people are mainly concerned about issues that affect the whole country or the planet. Here, the economy, politics and climate are at the top of the list. In contrast, the lower-status milieus and the middle-class milieus are primarily plagued by private existential worries.

And what about COVID?

This does not mean that awareness of the COVID pandemic has disappeared, however, as most people still express concern. A clear majority of Germans also continue to take the threat posed by the SARS-CoV-2 virus seriously, although attrition is evident: in March 2020, i.e., at the beginning of the pandemic, almost all Germans (92%) stated in a SINUS survey that the threat should be taken seriously. In March 2021, this value was slightly lower (86%), and it had fallen significantly by May 2022 (69%).

Moreover, people’s grounds for concern vary along with their basic orientations and milieu affiliations. For instance, members of the Post-Materialist Milieu are already likely to anticipate a challenging autumn. The Precarious Milieu, Nostalgic Middle Class Milieu, and Consumer-Hedonistic Milieu, on the other hand, are more concerned for their own financial futures.

In sum: Crisis resilience is milieu-specific

When the results are summarized in the Sinus-Milieu model, it becomes clear that general crisis resilience is very unevenly distributed in German society, and strongly dependent on milieu affiliation and social position. “Due to the current crisis situation, the social classes are increasingly drifting apart. Upper class milieus, such as the efficiency- and progress-oriented Performer Milieu or the cosmopolitan Expeditive milieu, are better able to cope with the current crises, they are more resilient. In addition, they usually have objectively better economic conditions. Both makes them think and feel more optimistically. This optimistic attitude is also accompanied by an above-average trust in media and journalism,” said Manfred Tautscher, Managing Director of SINUS-Institut in a press release at the end of May 2022.

Next steps in COVINFORM

Currently, the COVINFORM project is in the midst of qualitative research on personal experiences and narratives of the pandemic among a number of vulnerable population groups, including low-socioeconomic-status women in cities across Europe. In Germany, we focus on low-socioeconomic-status women with and without a migration background, living in vulnerable neighbourhoods in the city of Mannheim (in order to better understand the role of gender in pandemic experiences, we are also interviewing men with similar backgrounds). Previous project phases have focused on the governance, public health, and civil society factors involved in COVID-19 responses nationwide and in Mannheim in particular; the current phase focuses on how these responses have shaped people’s everyday lives.

In the interviews conducted so far, it has become clear that many of society’s most vulnerable have experienced COVID-19 and the war against Ukraine less as two unrelated events, and more as overlapping “threat multipliers” that have exacerbated numerous pre-existing concerns caused by structural inequality (Huntjens & Nachbar 2015).

The COVINFORM consortium hopes that the heterogenous insight we generate will assist policymakers and civil society institutions to plan resilience-building strategies that more effectively account for the role of social inequality in the experience of overlapping crises.

Authors: Tim Gensheimer and James Edwards, SINUS-Institut

References

Barth, B., Flaig Berthold, Schäuble, N., Tautscher, M. (Hrsg.): Praxis der Sinus-Milieus – Gegenwart und Zukunft eines modernen Gesellschafts- und Zielgruppenmodells. Springer Fachmedien, Wiesbaden 2018, ISBN 978-3-658-19334-8.

Hradil, S.: Soziale Milieus und Lebensstile: Ein Angebot zur Erklärung von Medienarbeit und Medienwirkung. In: Klaus-Dieter Altmeppen, Thomas Hanitzsch, Carsten Schlüter (Hrsg.): Journalismustheorie: Next Generation. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2007, doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90401-6, S. 165-212.

Huntjens P & Nachbar K. (2015).Climate change as a threat multiplier for human disaster and conflict. The Hague Institute for Global Justice.

Reckwitz, A. The End of Illusions: Politics, Economics and Culture in Late Modernity. Polity, Cambridge 2021.

Schulze, G.: Die Erlebnisgesellschaft. Kultursoziologie der Gegenwart. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt/New York 1992, ISBN 359334615X.

Vester, M.: Milieuspezifische Lebensführung und Gesundheit. Health Inequalities: Jahrbuch für Kritische Medizin und Gesundheitswissenschaften, Band 45, 2009, ISBN 9783886198245, S. 36-56.

[1] These dimensions are operationalized by means of a validated questionnaire, the Sinus-Milieu indicator; by applying this indicator within a survey, the milieu composition of a sample can be ascertained. Note that the boundaries between milieus are fluid: SINUS-Institut calls this the ‚blurred relations of everyday reality‘.